Contact Manager

Phone:

+64 21 620 456

16 Kauri Street, Woburn, Hutt City, New Zealand

email:

Manager@virtual.co.nz

|

The public sector has major issues

By Bruce Holland

Regulation today reaches into every aspect of our lives, from paying the gas bill to phoning a friend or using a credit card. Yet despite its achievements, the regulatory state is on the brink of a crisis. The current model of public policy making is no longer right for any government that has set itself the challenge of delivery.

Our society is a mess and it's partly due to the public sector

Our society is a mess. The doomsday clock is only minutes from midnight. We need to change. As Einstein said, we can not solve the significant problems we face today with the same thinking that gave rise to them.

The process we have been using is called reductionism. It involves breaking down anything being examined into the parts that make it up. From that we can learn how things work. If you take a mechanical clock to pieces, you can see what each part does and you can find out how it works.

There is no doubt that science has made enormous progress largely by ignoring the complexities of the world and focussing on the simple questions, looking to explain straight-line issues like why apples fall to the ground and why the Sun rises in the east.

Some of the world is like that, otherwise the orbits of the planets could not be predicted; nor could a spacecraft be launched that would land on Mars. Most things, however, can't be investigated in this way. There is much to be learned by dissecting a rat, for example, but in dissecting it, we kill it and cannot know what gives it life. So, by the middle of the twentieth century most of the simple questions had been answered and scientists began to lose their innocence and naiveté about how the world works and turned to more complex questions and these are the stuff of complex adaptive systems and systems thinking.

We now know that most of the world dances to a non-linear tune, that is not easily understood with standard mathematics. Weather is the classic example; so too are nearly all the issues our public sector needs to solve.

There are issues in how our public sector is structured

Despite the fact that scientists have known about this for decades the current public sector is basically straight-line. Just think about the way we have traditionally organised public sector work in bureaucracies or silos.

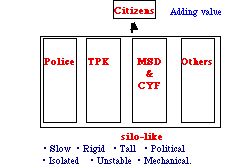

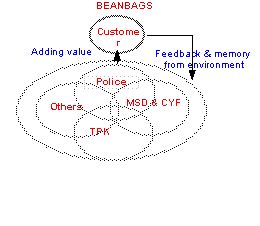

I have used Child,Youth and Family as an example, not because It's a problem agency, indeed I suspect CYF is better than most agencies at working as part of a wider system; rather it is because I have been working in this area for some time. If we were drawing them it would look like:

For example when we provide social development to citizens, we organise the various organisations involved (Police, Te Puni Kokiri, Ministry of Social Development, and lots of others) in silos that are poor at talking together and at considering the individual and asking the simple question: "How can we together help this citizen?". Rather they all push their own programs with little respect or understanding of what the others are doing.

There are three main problems with being siloed:

- Public managers charged with manipulating or, worse, managing complex systems can not control systems the way they might a simple (or even complicated) system. Rigidly hierarchical organisations directed through topdown decision making are likely to be ineffective.

- In silos people tend to focus on themselves or their teams, or their agencies. Almost by definition people in silos are not working for the benefit of the Sector at large. Often people do things that seem beneficial at the lower level but destroy value from the whole. This includes fighting each other and competing with each other for resources and power.

- The way the public sector is structured directly impacts on the way it thinks and therefore on the policies and decisions it makes. Anyone who has worked in a bureaucracy knows how difficult it is to think outside the square, let alone, outside the organisation. Indeed the whole rationale of a hierarchy is to deliberately reduce system variation and in favour of control and topdown, linear thinking.

The beanbag alternative

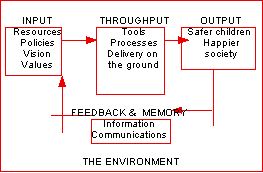

The alternative is government based on systems thinking, a better model for change in complex systems such as the public sector.

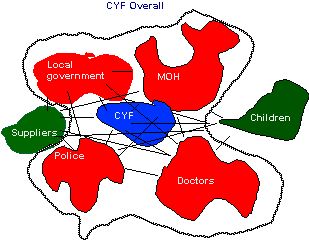

This living system includes many publicly and privately owned organisations that are all broadly working towards a similar end, to protect the country's children and make stronger families. Each part of this network is connected to the other parts (or should be), and each part depends on the other parts for its success.

This is CYF's primary system, its primary focus and the components as its strongest P.A.L.s (partnerships, alliances and linkages). The work of CYF is to make this system work.

Just imagine the additional value they could add if the Sector was organised like a beanbag!

Beanbag is the name I like to give to organisations formed as complex adaptive systems.

Imagine if the various agencies had porous, flexible walls that allowed information, relationships and other resources to flow between them more freely.

Imagine the structure was more flexible so they fitted exactly to the environment, no matter how much it changed; rather than the thick, impervious, solid walls of silo-like organisations.

Imagine the individuals inside were free to move far more easily to add the most value to customers no matter how much the environment changed; rather than being fixed in jobs and silos of power.

Imagine if public sector managers stopped competing and started cooperating with each other across the Sector; or even within the organisation. In this regard beanbags apply within each Agency also, with all discipline (Operations, Information and Support, Innovation and Customer service) working with cooperation, openness, feedback and memory.

Imagine if the Sector had fast, regular feedback that told it whether or not it was getting closer to its objectives or further away.

Imagine if the Sector memory was powerful and reliable so everyone learned from the practice of everyone else and built on this.

Imagine if, instead of inventing new policies for every new problem, our public sector managers went out and identified things that were already working well in the system and gave these exposure and resources to amplify them.

Imagine if our public sector managers understood that close to chaos small changes can lead to almost unbelievably big results. And, like the broken windows in New York, they went out searching for these small things and made them happen.

Imagine if our public sector managers learned how to use Agency-Based Modelling, and as a result were able to identify the simple decision rules that are pushing some sectors of the population into crime, drugs and poverty; then did something about changing the rules.

Finally, imagine if our politicians believed they were custodians of a living system, rather than an economic machine. They would stop selling off businesses or buying them back; they would stop the endless cycle of centralising and decentralising; they would stop structuring and restructuring; tinkering backwards and forwards with the detailed mechanics every time a government changed. Rather they would start preparing the soil for the citizens to plant and grow in the best overall conditions. They would allow the system to move naturally towards its "sweet-spot" that can only be interfered with by over-management.

- "Some people say I'm a dreamer.But I'm not the only one."Imagine. John Lennon

There are issues in how our public sector thinks

Most of the important problems today were born from reductionist thinking and this is how we are still trying to solve them. For example we are fighting terrorism, criminality, cultural conflict, environmental degradation, ill-health, even obesity and poverty with the same thinking that created them.

Just take a couple of these issues:

- We fight terrorism by tightening security. As a result we fight terrorists rather than terrorism. We are fighting the symptom rather than the cause. The trouble is, this approach only spreads it. A systems solution would look at the reasons why terrorism exists and try to fix the system.

- In the same sort of way, we lock up criminals and misfits in our society. This gets them out of sight temporarily but does not lead ultimately to safer communities because in jail they only learn more antisocial behaviour. A systems approach would target the lack of education and opportunity that leads to most antisocial behaviour.

To solve the big issues, we need to stand back and look at the whole system to understand how things work, rather than break it into pieces. Looking at the whole is the essence of systems thinking.

There are three main problems:

- Policy initiatives assume a direct relationship between action and outcome. This is a false assumption. Public services are complex adaptive systems which are subject to the law of unintended consequences, so intervention can make problems worse. The government's energetic attempts to force change from the centre are becoming counterproductive. Preparing the soil then trusting in emergence would produce better results.

- Public managers undervalue feedback and memory; these are critical parts of any complex adaptive system, and our public sector will not work until feedback and memory are given a higher priority. Without feedback we are doomed to straight-lined growth, with feedback exponential growth is possible. This is why I am so happy to work with New Zealand's major feedback process, the Department of Statistics. It needs to be given far more prominence. When it comes to memory, we learn a lesson, forget it, then have to rediscover it again. Remember the oil crisis of 1973? Or the share market crisis of 1987? Given the changes in the economics of information, memory is potentially far more available than ever before and Google-like technologies make it easier to manage. A government that gave it due focus would reap major benefits.

- Intangible assets matter more than tangible assets in complex adaptive systems. Energy flows through our economy, mainly in the form of culture (human emotions), information and relationships; yet nowhere are these critical factors measured or managed. What we do, is to measure them indirectly as expenses rather than assets; and focus on GDP as if it was the best measure of progress.

Public managers involved need to "feel" the system, watch and understand patterns, open communication channels both within the system and outside. They need to appreciate the system as a whole, not just a perspective from one location within the system.

The Public manager's role needs to become more facilitative; facilitating associations of citizens and other social organisations in order to produce social goods and services. This role is not so much as a problem solver, as a partner towards solution making.

Public sector managers should think of themselves as a "switch". A switch between various parties who need to be part of the solution, bringing them together and facilitating them to work together more effectively and with better information. They need to become managers of information and relationships.

While this way of working sounds unfamiliar to most public managers, with a better understanding of how systems work, they are able to trust that new pathways to solutions will emerge.

Lessons for public managers

- Public managers work in a complex adaptive system. They are managers of an organic (living) system; they are not managers of a mechanical system. And this must become their whole frame of reference and world view.

- Network development skills are becoming more important so public managers can know and bring together the parties needed for a solution.

- Facilitation skills are replacing command and control so that the group can achieve shared leadership, consensus, and objectivity.

- The challenge is to understand the emergent properties of the wider complex adaptive system, feeling the flow, like a stream is felt with loose fingers, not a fist.

- Focus on feedback and memory, and the system will thrive.

Final comment

It's important to realise that I am not promoting systems thinking as an all-encompassing theory, taking over from straight-line approaches. Even Prigogine (who won a Nobel Prize for work in this area) insists that linear science and its models are not discredited by systems thinking; in conditions of great stability and for short time periods, linear approaches work well enough. The only trouble is, stability and short time periods are not the norm, especially today.

Bruce Holland

Virtual Group Business Consultants

Phone 021 620 456

Web site: http://www.virtual.co.nz

Bruce helps large mature organisations be more focused, fast and flexible. Places where people have more depth, connection and meaning.

"Liberating the Human spirit at work"